I’ve sat through countless conference sessions and meetup discussions about tech debt. Without fail, I find them boring at best and infuriating at worst.

For years, I couldn’t figure out why. The topic seems important enough. Smart people care about it. But every time the conversation starts, I feel my brow furrow, my head drop into my hands, and my attention drift to checking updates from my wife about our son’s evening routine.

A few weeks ago, it happened again (at the Tech Leaders Exchange). I was physically present but mentally checked out. But then fragments of conversation started cutting through the noise like a radio finding signal.

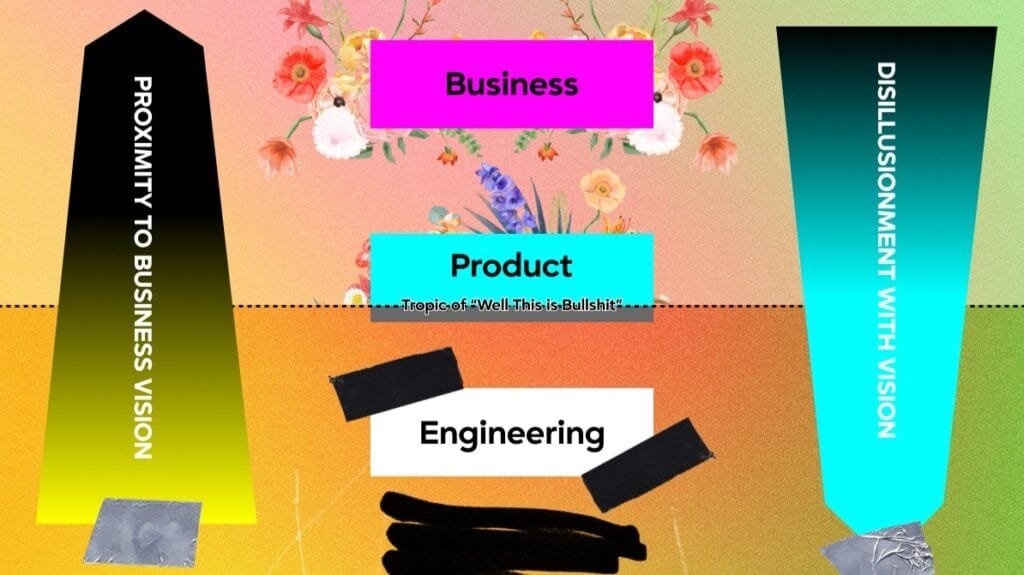

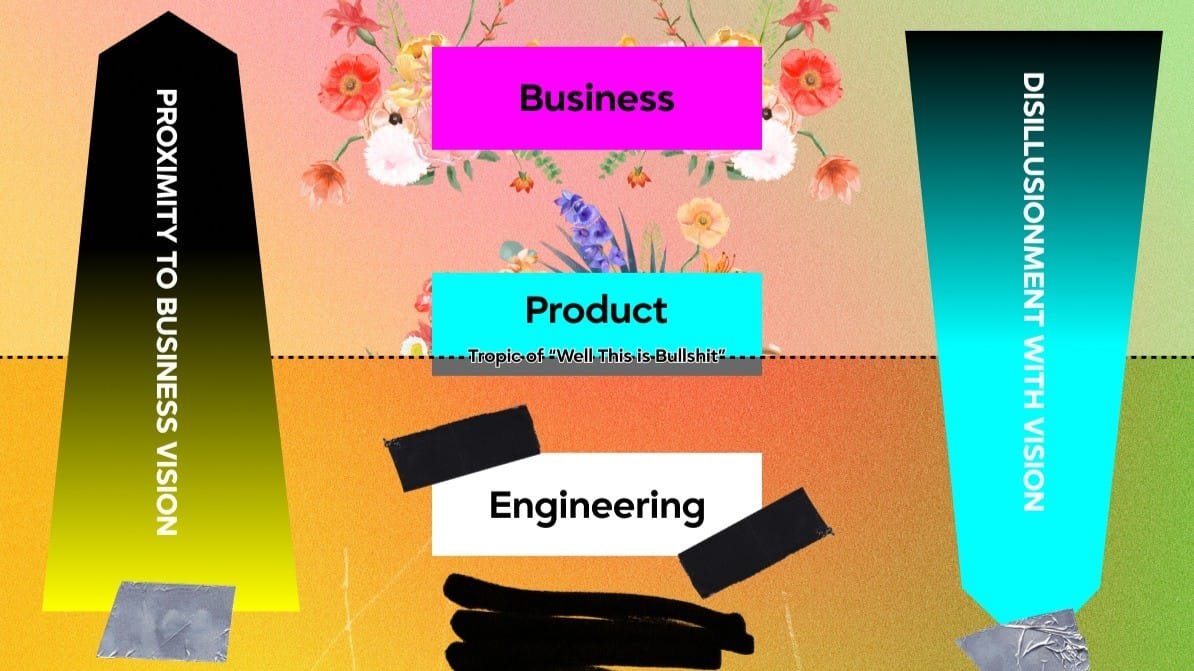

“…we need to explain the value to business…”

“…we struggle to get the other side to understand…”

“…business doesn’t care about tech and engineers don’t care about business…”

Us versus them.

Always us versus them.

And suddenly, clarity hit me like an out-of-body experience: Tech debt is a side effect of capitalism.

What Is Tech Debt Really?

The standard definition of tech debt is a future cost that we pay for making a technical compromise now. The reality is that a lot of tech debt is never completed; we never come back to it.

There are two reasons that we never come back to these things:

- We didn’t need to; the perceived risk/compromise that we felt we took didn’t materialise, and the compromise was “perfectly acceptable engineering”.

- We don’t have time to.

So, why don’t we find the time? Because the business won’t let us prioritise fixing these things over work that needs to be done for commercial reasons.

So tech debt is either things we shouldn’t be doing, or things that we couldn’t convince the business of the commercial value of.

But why can’t we do that?

The Real Problem: Purpose That Nobody Believes In

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: most companies peddle widgets while manufacturing a fake purpose to keep employees engaged. This is the capitalist way: the primary goal of the company is not to disrupt X or revolutionise Y; it’s to increase shareholder value. These are the simple rules that more of our society is based on.

Mission statements get wordsmithed by consultants, or more recently ChatGPT. Values get printed on posters. And everyone nods along in all-hands meetings while privately thinking,

“Cool, but I’m really here because I need health insurance and my mortgage won’t pay itself.”

Engineers, in particular, tend to smell this inauthenticity from miles away. When your company’s stated purpose is “empowering synergistic solutions for tomorrow’s challenges,” but you’re actually optimising ad clicks for a gambling app, something breaks inside. So engineers retreat to what feels real: the craft itself.

The elegance of the code. The architecture. The engineering. This was what brought us here in the first place.

Research on motivation consistently shows that people need genuine purpose to engage fully with their work. Dan Pink’s work on motivation identifies purpose as one of three core drivers of human engagement, alongside autonomy and mastery. When the company’s purpose rings hollow, people find purpose where they can.

And here’s where it gets structural: capitalism, in its growth-obsessed, shareholder-first form, actively incentivises fake purpose. Real purpose might mean saying “we shouldn’t build this feature” or “growth at all costs is destroying our product.” That doesn’t play well in quarterly earnings calls.

What happens when engineers can’t connect their daily work to something they actually believe in?

The Communication Gap Is a Values Gap

The standard narrative goes like this: engineers are bad at communicating business value, so they struggle to get buy-in for tech debt work. If only they’d learn to “speak the language of business,” everything would be fine.

This framing is cowardly nonsense.

The real issue isn’t that engineers can’t communicate value. It’s that they’re being asked to translate genuine technical concerns into a value system they don’t share.

“Business” (and I’m using that term loosely to mean the incentive structures most companies operate under) values what can be measured in quarters and reported to shareholders. Engineers often value sustainability, craft, and not being woken up at 3am because the system they warned everyone about finally collapsed.

These aren’t communication problems. These are value conflicts.

When an engineer says “we need to refactor this service,” and a product manager asks “what’s the ROI?”, they’re not speaking different languages. They’re operating from fundamentally different definitions of what success means. The engineer is thinking about system health over years. The PM is thinking about this quarter’s metrics because that’s what their bonus depends on.

Is the answer really that engineers get better at “speaking business”? No, it’s probably that we need to build companies where engineers perceive themselves as part of “the business”. Companies where they either care about the vision, or have a clear agreement that the core goal is dirty, stinking, filthy cash, and the individual has chosen to accept this as part of surviving in a capitalist world.

The System Is Working Exactly As Designed

Here’s the part that makes these discussions truly tedious: we keep treating tech debt as an engineering problem with engineering solutions, or an engineering leadership problem.

Better metrics. Debt registers. Refactoring sprints. Communication frameworks.

But tech debt accumulates because the system rewards accumulating it. Ship fast, hit targets, get promoted, move to the next role before the consequences arrive. The people who made the debt-creating decisions are often long gone by the time the bill comes due.

This is capitalism functioning exactly as intended. Externalise costs. Chase short-term gains. Let future-you (or future-someone-else) deal with the consequences. Tech debt is organisational climate change. We keep emitting complexity, cutting corners, and shipping fast because the costs are diffuse and delayed. By the time the system becomes unmaintainable, the executives who prioritised “velocity” have cashed out their stock options.

The uncomfortable admission: fixing this is genuinely hard. It requires companies to value long-term sustainability over short-term growth and quick financial returns.

So What Do We Actually Do?

I’m not naive enough to think we’re going to dismantle capitalism before next sprint planning. But I’m also done pretending this is a communication problem that engineers need to solve by getting better at stakeholder management.

Stop accepting fake purpose. If your company’s mission doesn’t connect to work you actually believe in, that’s a leadership failure, not an engineering attitude problem. Name it. Push back. And if nothing changes, consider whether you’re in the right place.

Refuse the “us vs them” framing. The next time someone talks about “explaining value to business,” remember we’re all “the business”. Look for ways to connect engineering and other disciplines better.

I do wonder if a push towards sustainable development would allow the engineering discipline to have a much more positive impact on the world. The values are so much more closely aligned with the core tenets of engineering.

Alternatively, maybe we need to move towards a model where we view code as more expendable, deletable, leveraging tools that allow us to build quicker to enable a much faster cycle time on the lifespan of software. If all the code we build is replaced quarterly, so is the tech debt.

Tech debt isn’t your communication failure. It’s a symptom of a system that treats people and codebases as expendable resources to be optimised for quarterly returns.

These boring conversations will stay boring until we’re willing to talk about that.

Things I’ve found interesting recently:

- I’ve been really enjoying the Radical podcast from the BBC; it presents challenging and enjoyable topics with a balanced view. The recent episode with Naomi Alderman talking about the “Third Information Crisis” is everything you want in a podcast discussion.

- Another podcast I’ve enjoyed recently was Leadership Confidential’s recent discussion with Cornelius Meister about conducting an orchestra and the parallels between conducting an orchestra and leadership.

Leave a Reply